Here in Spain, it’s beginning to look an awful lot like Christmas. In Madrid and Barcelona the lights are on, there is piped festive music in the streets and the department stores have gaudy displays in their windows. The markets are busy, too, as people shop early to beat the higher prices later on. As I write, in my country village in Extremadura one neighbour, Remedios, has already covered the wall of her house with flashing multicoloured decorations and installed two huge inflatable Santas on either side of the front door.

In the old days Christmas in Spain was never such a big deal. Among the various fiestas that light up the religious year, Semana Santa (Holy Week) was a much more important event in most people’s lives. Children received their presents not on Christmas Day, but at the feast of the Three Kings when Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar (or three local gentlemen got up in oriental costume and beards) parade through the streets of every Spanish town. There was no tree, no sparkly tinsel, no turkey on the table, and little of the consumerist paraphernalia of the English-speaking Christmas.

Thanks to television and globalisation, some of that has changed. The Spanish Christmas is more similar now to Christmases everywhere else than it has ever been. Lucky Spanish children now get the benefit of two gift-giving moments: first on Christmas Day, then at the Three Kings. Santa Claus is now very evidently a Thing.

But festive traditions, in this tradition-obsessed country, aren’t so easy to shake off. One custom that remains universal is the singing of villancicos (Spanish Christmas carols) – my personal favourite is the one about the Virgin Mary washing nappies in the river. Archaic local fiestas like the Olentzero, featuring the curious Basque mythological figure of a coal merchant who brings presents, are as popular as ever. Even in what is increasingly a secular society, midnight on Christmas Eve still sees the churches packed for La Misa del Gallo – ‘the cockerel mass’.

But where Spain really takes Christmas seriously is in the matter of eating and drinking. Statistics suggest Spaniards spend an average of 630€ on Christmas gifts, decorations and other accessories, with around a third of that amount going on food – a bigger outlay than in any other EU country.

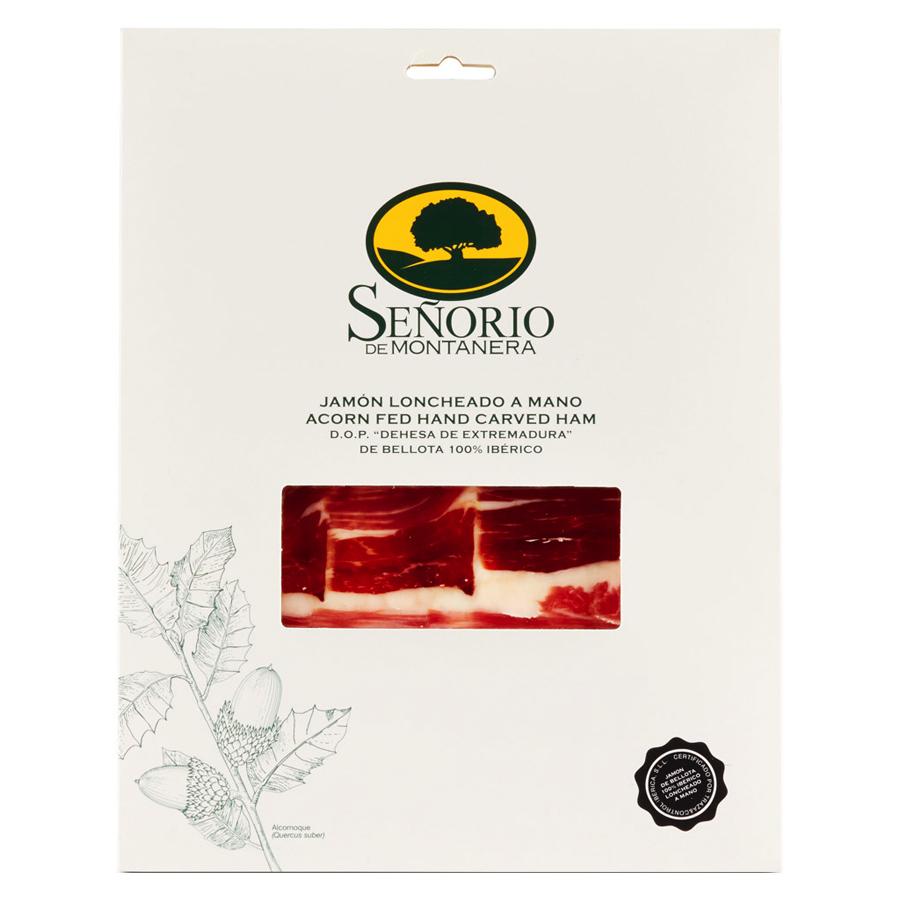

Frugal for the rest of the year, Spanish households will typically empty out the piggy-bank for prestige edibles such as acorn-fed jamón ibérico (some families buy a whole ham and work their way through it over Christmas and New Year), shellfish, fine cheeses, and fancy confectionery (more on that later). The seasonal spend on wines and spirits also rockets, with a particular emphasis on cava, which comes into its own as the festive tipple por excelencia.

Spanish life in general has close ties between fiesta and food, and Christmas is no exception. When it comes to the menu for dinner on 24th December, ground zero of Spanish yuletide celebrations, the menu spills out into endless variants. The feast might begin with a soup, often fish-based, or cold platters of prawns and langostinos. In vegetable-loving regions like Navarra and La Rioja a popular first course is cardoons with almond sauce, while in my house a much-loved standard is red cabbage braised with apples and pine nuts.

Then comes the main dish. This is commonly a roast leg of lamb or a suckling pig, but in Madrid and in other parts of the country it’s more likely to be an oven-baked sea bream or bass. Nothing is set in stone: in my three decades of Spanish Christmases I’ve seen such exotica as stuffed capon, truffled roast chicken - even turkey. The ruling bird of anglo-saxon Christmas is finally making major inroads on the Spanish festive table, where it already had a niche in the form of pelotas de pava, a dish of turkey meatballs with pinenuts, lemon and herbs, hailing from Murcia.

Catalunya is a case apart. Here the emphasis is less on Christmas Eve dinner and more on Christmas Day lunch, when tradition demands the full-on escudella i carn d’olla – a luxury version of cocido including chickpeas, various mixed meats, vegetables and pilotes (meatballs). This is eaten in two courses: first a rich consommé with pilotes and galets (large floppy pasta shapes) followed by the chickpeas and meats. (Any leftover meat being recycled in the stuffed canelons made on the feast of Saint Stephen, which we know as Boxing Day.) After which comes a post-prandial sobremesa stretching long into the afternoon with glasses of moscatel, lashings of cava, and a selection of almond-based goodies bought at the local confiteria.

And if there is one thing that defines the festive season in Spain more than anything else it’s the massive consumption of sweetmeats. Christmas tables here are a groaning board of biscuits and chocolate and marzipan and nuts, as well as old-fashioned specialities like mantecados and polvorones – both types of crumbly macaroon made with ground almonds, flour, sugar and pork fat, sometimes flavoured with cinnamon, chocolate or red wine. Spanish housewives dutifully buy them by the sackful when Christmas comes round, yet in my experience these dry and dusty little biscuits tend to linger sadly on the table long into January.

Turrón in all its forms tends to disappear much faster. This is surely the king of Spanish sweeties, and a symbol of festive excess that unites the country from one end of the peninsula to the other. Turrón is based on almonds, egg whites and honey and traditionally comes in two forms: turrón de Alicante, a hard candy with whole almonds, and turrón de Xixona, a dense sticky paste of toasted ground almonds bound together with honey. As you read this, Madrid’s most famous turrón shop, Casa Mira in the Carrera de San Jerónimo, has queues out the door and down the street. In recent years turrón manufacturers have got seriously creative and you’ll now find variations based on hazelnuts or walnuts, with puffed rice and chocolate – there’s even a ‘crema catalana’ version complete with its caramelised topping. For me, however, the original ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ styles (like those made by Alemany and sold by Brindisa) are still the best.

Just like the UK, Spain has its favourite Christmas TV adverts. The Freixenet cava ad is a big production number often featuring celebrities and TV stars. Another classic one, for a well-known commercial brand of turrón, repeats the same message year after year. Ask any Spanish person and they’re bound to know the ad’s famous jingle, which goes ‘vuelve a casa, vuelve por Navidad’.

‘Come back home, come back for Christmas’. It’s cheesy, but right on the nail. Because what’s really important about Christmas in Spain is not the conspicuous consumption or the complex traditions, not the free-flowing cava and the slabs of turrón, but the simple fact of getting the family together around a table.

Brindisa Bellota 75% Iberico Ham Kit

Brindisa Bellota 75% Iberico Ham Kit 100% Iberico Hand-Carved Ham

100% Iberico Hand-Carved Ham Cooking Chorizo

Cooking Chorizo Freshly Sliced Charcuterie

Freshly Sliced Charcuterie Truffle Manchego

Truffle Manchego Galmesan Wedge

Galmesan Wedge Beech Smoked Anchovies

Beech Smoked Anchovies Perello Manzanilla "Martini" Olives

Perello Manzanilla "Martini" Olives Apple Cider Vinegar

Apple Cider Vinegar Perello Chickpeas

Perello Chickpeas Buy a Gift Card

Buy a Gift Card Celebration Hamper

Celebration Hamper Sherry

Sherry Sparkling Cava for Christmas

Sparkling Cava for Christmas Perello Olives

Perello Olives Navarrico Butter Beans

Navarrico Butter Beans